Often, travel to any place of our choosing is as simple as a few clicks of the mouse or, better still, a few swipes of our fingers on our smartphones. Convenience is king and control is paramount to the modern-day consumer. Platforms like Booking.com, MakeMyTrip, Tripadvisor and other similar web-based services allow us a degree of command that we cannot imagine living without.

These services we see today have evolved over the last two decades and quite remarkably in the last ten years. But airlines and flight services have existed from the 1950s and hotels even longer still. How, then, did the masses plan their travel, block aircraft seats, and book their preferred suite at their favourite hotel?

Let’s take a trip down memory lane and rediscover what came before the advent of the ‘online travel agents’ (OTAs).

Travel had become an integral part of the post-World War II economic and social landscape. American Airlines, PAN American, Lufthansa, and British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) were among the first airlines to start operating commercial flights. In 1955, for the first time, more people in the United States travelled by air than by train. By 1957, airliners had replaced ocean liners as the preferred means of crossing the Atlantic.

This sudden spurt in travel and tourism led to the rise of businesses that assisted people in their travel planning. Although they had existed for a long time, travel agencies became a lot more prominent during this period. While delivering other travel related services, these agents also acted as an intermediary between travellers and airlines. At a time when computing technology was non-existent, travel agents maintained manual records of flight schedules and liaised with airline operators for booking flight tickets for their clients.

The sudden growth in passenger traffic perplexed airline companies. Airlines used an obsolete manual system to access their flight inventory and block seats for passengers and travel agents who called over the telephone. It took almost an hour to process one flight reservation.

American Airlines, with the help of IBM, was among the first to develop a computer reservation system (CRS) to simplify the booking process at a time when flight traffic was growing exponentially. The ‘Semi-automated Business Research Environment’ popularly known as SABRE, was the first of its kind ticketing system to be developed. Its function was to act as a middleman between a travel agent and an airline’s reservation system. Travel agents could see real-time rates and inventory for a given airline via the CRS, though the CRS does not actually hold its own inventory. It simply acts as a window into the airline’s system.

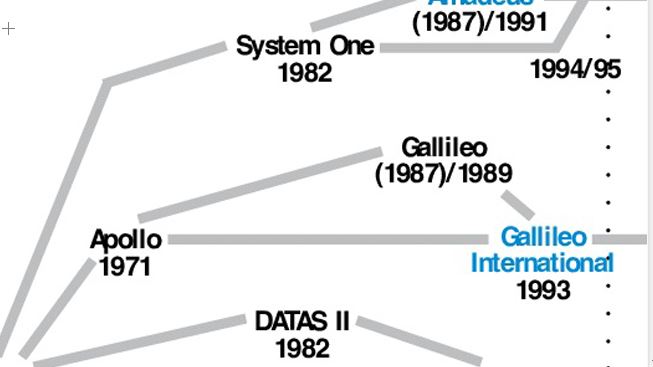

By the time it was put to use in 1964, SABRE could process 7,000 bookings an hour. Taking a leaf out of SABRE’s successes, other airlines also developed similar platforms for flight bookings and soon there were multiple CRSs operating across different airlines and countries.

By the early 1970s passenger movement continued to grow and the world became a smaller place. Still, one issue continued to plague flight operators: despite the new computing system, their on-ground team still found it difficult to handle the ever-increasing demand for flight bookings. Phone calls from travel agents and passengers were still far more than their workforce could cope with.

The solution was as ingenious as it was simple. If a hundred thousand people had to book flight tickets by reaching a hundred travel agents, why should a team of twenty, sitting at an airline office process all those bookings? An easy fix – hand over your terminal to the agent! And that is exactly what the airlines did. They allowed travel agents access to the CRS software and charged them a fee to do their job for them.

In 1976, United Airlines (Apollo) and American Airlines (SABRE) started selling access of their reservation systems to travel agents. Delta, Trans World, and Eastern joined the movement soon. Travel agencies now had to choose which airlines they wanted to work for. Each carrier offered travel agents a long-term distribution contract on a monthly fee basis. They also provided training on installation, software maintenance, and operation.

With the deregulation of the airline industry by the US Government in 1978, big airline companies started selling access of their state-of-the-art ticketing software to other smaller carriers by charging a fee. Soon, almost all flight operators had access to the CRS and thereby to a bigger customer base. This led to the emergence of the term Global Distribution System (GDS).

Soon after, European airline operators also adopted a similar GDS model with the formation of Amadeus and Galileo. With time, smaller GDS operators merged with their larger counterparts and after multiple changes in this ecosystem, the three main GDS operators emerged that still dominate world travel today: Amadeus, Sabre and Travelport (Galileo, Worldspan and Apollo).

After having proven its success with airlines, the Global Distribution System started being adopted by hotel companies from the 1980s. This new technology allowed hotels to reach out to potential guests and sell more rooms. Travel agents that had access to a GDS could not only use it to book flights for its customers but now also hotel rooms.

For both hotels and airlines, the GDS offered massive marketing power. Before the GDS became popular, hotels would need to undertake huge marketing efforts in order to be seen by travel agents. The GDS effectively democratized this process, with chain hotels getting the same visibility on the GDS as independent hotels. The GDS also gave hotels access to a new segment of corporate travellers via companies like American Express and Carlson Wagonlit, who likely would not book directly with the hotel.

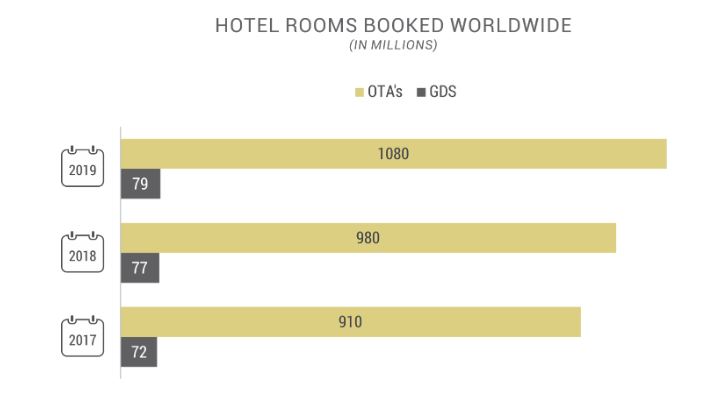

The next two decades saw extensive use of the GDS. However, things started to change with the advent of the worldwide web and its mass adoption from the start of the twenty-first century. In 2006, the volume of internet reservations exceeded GDS reservations for the first time, thanks to the growing popularity of online booking channels. The new millennium also witnessed a sea change in consumer behaviour. Fast internet speeds at affordable prices; access to gigabytes of information; personal accounts of people’s experiences in the form of blogs and, more recently, vlogs; and a digital social structure driven by Facebook, Instagram and Twitter were all made possible by the internet revolution, hugely impacting how people conceive and execute their travel plans.

Source: TravelClick

Travel agencies have also had to adapt to a world where technology has empowered the common man to do everything that was once upon a time ‘left to the experts’. Flight ticketing, once a major revenue generating streams for travel agents, is now a mere trickle. Today, travel agents leverage personalised service as a selling point for their business. They collaborate with travellers to satisfy individual preferences and can leverage personal relationships with suppliers, like hotels and airlines, to deliver a better travel experience.

In an equivalent manner, the GDS has also learnt to customise its offering and become business-to-business (B2B) centric rather than business-to-consumer (B2C) centric. Having said that, airlines continue to use the GDS to distribute their inventory to online travel agents and corporate travel planners, and big business organisations continue to use the GDS to process their corporate bookings. Travel agents also use the GDS to process bookings either for their corporate clientele or for bulk or multi-city bookings. Among travel agents however, B2C bookings over the GDS have dropped dramatically since the online travel agency revolution.

To conclude, despite the changing trends and the dominance of the internet economy, the GDS has not lost its footing. In fact, its usage has gone up in recent years largely due to the growth in corporate travel. To sustain its competitive advantage, however, the GDS must find ways to reinvent itself. Recognising the volume of data the GDS has access to, its operators have developed data analytics tools like traveller demographic preferences, booking and market trends and so on. These tools can be purchased by hotels to acquire market intelligence and insights that can be utilised to maximise revenue. It goes without saying then that innovation is the key to the GDS’ survival in the long term.

Despite what the future may have in store for it, the GDS will always hold the tag of being the first computing machinery that facilitated travel for millions around the world. It is in many ways a precursor to the technology that has made our lives incredibly smoother and more efficient, and its legacy is worth remembering.

https://hotelivate.com/hotel-operations/evolution-of-the-global-distribution-system-gds/